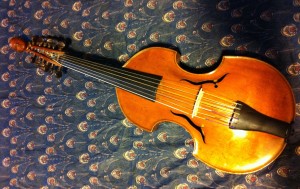

The subject of Bach’s inclusion of certain unpopular and nearly obsolete string instruments (lute, viola d’amore, bass viol) in the St John Passion has long been a subject of scholarly interest. By 1724 all three instruments were considered old fashioned by his contemporaries, and in later versions of the St John Passion Bach replaced the viola d’amore with muted violins. However Bach’s original choice of instrumental accompaniment was not without consideration of the instrument’s own rich imagery and associative function. It is believed Bach featured the bass viol in the alto aria ‘Est ist vollbracht’ (‘It is fulfilled’) because the instrument was thought to be identified with Lutheran sentiments attributed to the ‘sweetness of death’. For similar illustrative purposes, it is believed Bach originally chose the lute and the ethereal sound of the viola d’amore to express the meditative aria ‘Betrachte, meine Seel’ (‘Reflect, my Soul’) and ‘Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken’ (‘Consider how his blood-tinged back). When considering the importance of these instruments, the ‘Erwäge’ aria is a perfect illustration of Bach’s choice. The rainbow in the aria makes for one of Bach’s most beautiful pictures in music, and is immediately reflected in the notes which make a definitive arc repeated throughout the movement. The rainbow imagery of the aria is also repeated in the distinct structure of the seven-stringed d’amore, complementing the idea that the seven colours of the rainbow are represented by each string.

For this week’s Passion blog, we are fortunate to have AAM orchestra members Jane Rogers and Pavlo Beznosiuk share why they believe that the St John Passion would not be the same without the viola d’amore.

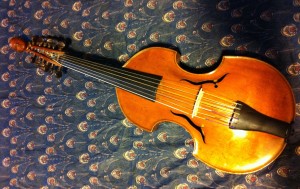

Viola d’amore, made in 1757 by the English maker John Marshall

Jane Rogers

“Initially I came to play the viola d’amore at the request of a colleague — and somewhat reluctantly I might add as it is a notoriously complicated instrument! My story begins twenty years ago: we were about to perform the John Passion with Florilegium and Trinity Baroque, and Julian Podger (who was directing the project) decided that he would like to have violas d’amore playing numbers 19 and 20 rather than muted violins (which Bach resorted to in his later revisions of the piece). Rachel Podger and I managed to borrow a couple of d’amores and taught ourselves how to play these strange and wonderful instruments in the space of about a week.

“The viola d’amore has a most distinctive sound. The sympathetic strings which lie underneath the strings which are bowed resonate wonderfully to create a bitter-sweet, haunting and almost unearthly sound. The way in which you tune the strings and the angle at which they sit on the bridge of the instrument allow for easy execution of chords further adding to the resonance of the instrument. The dimensions of the viola d’amore aren’t really standardised and so differ quite a lot between instruments. Some have a longer or wider neck or are deeper in the body making them more difficult or easier to play depending on your own physiology.

“Word then seemed to get around that I was suddenly some kind of authority on the instrument and people just kept asking me to play concertos and other pieces involving it. I often felt quite awkward about this because I didn’t own an instrument and couldn’t at that time really afford to buy one. Luckily Roy Goodman said I could always borrow his as he rarely used it, and for the few concerts per year that it was needed this arrangement worked well.

“Two years ago I was asked by the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra to play the d’amore in their St John Passion tour (13 concerts in a row!). Roy’s d’amore wasn’t available so I replied to the orchestra agreeing to play on the condition that they found me an instrument in Holland. I secretly hoped they wouldn’t be able to find anything and would have to opt for the muted violin version, as touring the John Passion can be logistically a bit of a pain for the d’amore player, because you have to carry around your viola as well as your viola d’amore and the rest of your luggage. Most airlines won’t allow you on the flight with two instruments which necessitates bribing some unsuspecting member of the choir or a keyboard player into carrying one of the instruments for you. On this particular tour we had a flight (sometimes two) every day. Stephaan, the tour assistant, got on the case and found three instruments from which I could make a choice. I then had to decide, without seeing any of them, which one sounded most promising.

“I turned up three hours before the first rehearsal in Amsterdam to hurriedly get acquainted with the instrument and I was most pleasantly surprised. He had found a viola d’amore made in 1757 by the English maker John Marshall. It had been most kindly loaned by Bouman violin shop in The Hague and all the orchestra had to do was pay the insurance.

it feels like an old friend and I have the distinct sensation that its presence and participation in the coming project is a thing meant to be.

“It was the first time I felt a real affinity with an instrument from the moment I picked it up. It was just perfect. This instrument felt really comfortable and easy to play-easy isn’t a word you naturally associate with the viola d’amore given its odd shape and all those extra strings you have to tune! I had a lovely time getting to know the instrument on that tour and was sad to hear on returning it that it wasn’t for sale. I did ascertain, however, that I might be able to borrow it again if needed.

“When AAM announced its intentions to perform and record the John Passion and I was asked to play one of the d’amore parts I knew immediately that I wanted to borrow the Marshall — it really felt like nothing else would do. The problem was how to transport it from Holland to the UK. We racked our brains on how to do this without specifically forking out for a return flight in one day and it was all looking a bit difficult. Andrew Moore (our Orchestral Manager) and I came up with a somewhat complicated plan that involved me leaving Paris at the end of one tour at 6.30 am to get to the Hague for 9am, collecting the instrument and meeting up with the rest of the orchestra at Schiphol airport to get the bus to our concert in Groningen (North Holland) later that day. Out of the blue on the morning that we were about to book the train ticket I got a message from a friend Marcin who just happened to live in the Hague on the same street as the violin shop! He had miraculously remembered me mentioning in passing several months previously the need to transport the instrument and was coming to London to play a concert the following week — and strangely enough he was coming to play with Rachel Podger, my first St John Passion partner!

“As I write this, the viola d’amore is sitting next to me having arrived only two days ago. I’m just delighted to see it again — it feels like an old friend and I have the distinct sensation that its presence and participation in the coming project is a thing meant to be. I am so looking forward to playing it. I’d like to thank Lies Bouman of Bouman violin shop Den Haag for her generosity and trust in lending this beautiful specimen of one of the most characterful members of the string family.”

-

-

Viola d’amore, made in 1757 by the Englishman John Marshall

-

-

The beautiful carved head of ‘blind cupid’

-

-

Side view of the 7 bowed strings and 7 sympathetic metal strings underneath the main set

Pavlo Beznosiuk

“I’m delighted and privileged to have secured the loan of a particularly fine viola d’amore for the AAM St John Passion recording. I’m very grateful to the Royal Academy of Music (it is part of their collection) for allowing me to use this instrument by Thomas Eberle (1727-1792) a violin maker who was born in Austria but settled in Naples early on in his life and probably studied with Nicola Gagliano, arguably the most important member of this Neapolitan dynasty of luthiers.

“I’ve just had the instrument for a couple of weeks — a “get-to-know-you” period which is very important when trying out an unfamiliar violin, but doubly so when finding one’s way around a viola d’amore, familiar or not. The instrument has 7 strings which are bowed and 7 sympathetic metal strings which sit underneath the main set and vibrate naturally whenever a consonance occurs. It is this extra set of strings and its viol-like structure which give the d’amore its unique and distinctive colour, plaintive, silvery and other-worldly.

“In the John Passion this is used in the aria “Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken”, a meditation on Jesus’ agony on the cross. The plethora of strings makes tuning rather a palaver, especially if you feel it necessary (as I did) to change the gauges of some of the strings, partly to increase the tension slightly but also to adjust the relative levels of the strings on the bridge.

It is this extra set of strings and its viol-like structure which give the d’amore its unique and distinctive colour, plaintive, silvery and other-worldly.

“On a bridge with 7 seven strings the line on which you draw the bow (a tangent to the curve of the bridge) without touching strings on either side is a matter of pinpoint accuracy, a change of 0.1 of a millimetre in the gauge of a string can change things radically. So this is how my week has been spent, experimenting with different strings, different bows, an exercise in geometry as much as anything else.

“It’s a joy to play this aria on such an instrument and I have an added bonus this time as I get to play the top part, having played the 2nd part twice on past recordings (John Eliot Gardiner and Philippe Herreweghe). I’m looking forward now to playing Bach’s incredible music on this wonderful instrument.”